* This article was written by the late Alan Lott, circa 2000. It was originally published in Amateur Cine Enthusiasts magazine (ACE). It was later reproduced in Reel Deals magazine with the permission of the Author and ACE.

It is published here with the permission of Mr. Lott’s Family.

While this is an excellent situation for Canadian archivists and historians it has the unfortunate effect of locking away from the private collector all of the duplicate copies being handed in. One case cited in Ref 16 concerns seven copies of the same film handed in to the Archives. Once handed to the Archives they become national property and unavailable although this is done with the best possible motives.

I have managed to acquire a copy of Ref 17, which consists of 99 pages. The introduction carries the misleading statement "The originals are 28 mm black and white silent and are on safety film stock". Remembering that 28 mm did not come into general use until 1914 and the catalogue covers the period 1907 to 1930 the 28 mm films can not all be originals but are printed down from 35 mm at least up to 1914 after which date SOME would have been filmed on 28 mm camera stock. Most of the films listed are documentary / educational such as "Making Pig Iron" to "The Hermit Crab". Activities in foreign countries are also covered such as "Vintage in Burgundy" and "Salt Industry in Sicily". A section entitled Movies lists various entertainment films such as "The Gambler" and "That Model from Paris". Chaplin is much in evidence.

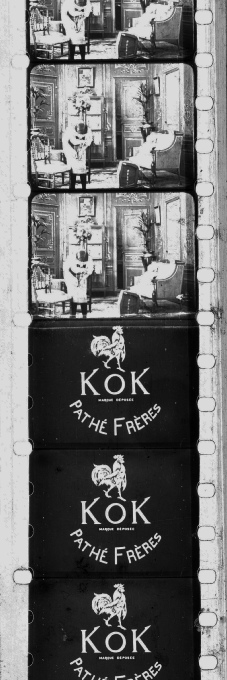

In the UK our National Film Archives, originally at Aston Clinton, but now relocated at Berkhamstead has a copy of the American Pathescope Film Catalogue the original of which is held at their London Office of the British Film institute; currently they have some 200 films on 28 rnm including several Max Linder comedies.

28 mm in the UK today.

In February 1983 I tried to discover how many 28 mm owners there were in the UK, other than professional institutions. (Ref 18). Additional to myself there were at that time only twelve. In addition I had four replies from abroad. From Australia one (Mike Trickett), from Holland one, and from the Netherlands two. All of these had KOK projectors nearly all with the rewind gear missing. The number of 400 ft reels of film (or equivalent short lengths) in the UK totaled 48, of which I have five and one person had thirty! Of that 30, half were loose coils without reels and so I arranged for a number of 400 ft 16 mm reels to be converted to 28 mm by fitting new specially made brass cores so that the films could be projected.

Although most of the 28 mm films in the UK are black and white I have seen one film tinted sepia, overall, and another tinted salmon pink. Subject matter varies widely from the Pyramids of Egypt and Salmon Fishing to such slapstick comedies as "No More Bald Men". There appears to be no communication between 28 mm owners and so no opportunity to see their films; once people acquire them they tend to regard them as precious items not to be allowed out of their possession; understandable but unfortunate.

It is something of a mystery as to what became of the bulk of the KOK projectors imported into this country from 1912 onwards and the contents of the film libraries administered by Pathescope and Houghtons of London.

Hopefully this article will arouse some interest and result in more projectors and films (also rewinds and splicers?) coming to light.

References.

1. "Film Gauges, Widths and Perforations during 77 Years of Motion Pictures" by Baynham Honri. British Journal of Photography, 23rd June 1972 pp.526-

2. "The Fascinating History of Cine Film Gauges" by Harry Waiden (source not known) pp 10 -

3. "Motion Picture Film Widths" by Kemp R Niver. Journal of the SMPTE August 1968 pp 814 -

4. "Historical Note – Motion Picture Film Widths" by H Tummel. Journal of the SMPTE January 1975 Volume 84 pp 24.

5. British Patent No.3048 French application 27th November 1911. U K application 6th February 1912 -

6. "Film Collecting" by Gerald McKee, Tantivy Press 1978. pp.49.

7. "The Pathescope Home Cinema" British Journal of Photography. March 14th, 1913.

8. "The Origins of the 28rnm Film System" Amateur Cinematographer, Paper No.1 1st Edition August 1983 by Stephen Herbert.

9. "The KOK and 28mm Movies" by John Minnis. Date and publisher not known.

10. "Additional Notes on 28mm" by John S Carroll. Date and publisher not known.

11. "Alexander F Victor -

12 "The Cinema Handbook" pp 414 -

13. "The Amateur Cinema" by Val Randall pub. Val Randall, Banstead, Surrey 1977. pp 5.

14. "Embattled Shadows" A History of the Canadian Cinema 1895 -

15. "Pathe's Home Cinematograph" by Kinelopath Lid., Film House, 251a Pitt Street, Sydney. Circa 1914. Pub. Turner & Henderson Ltd., Sydney.

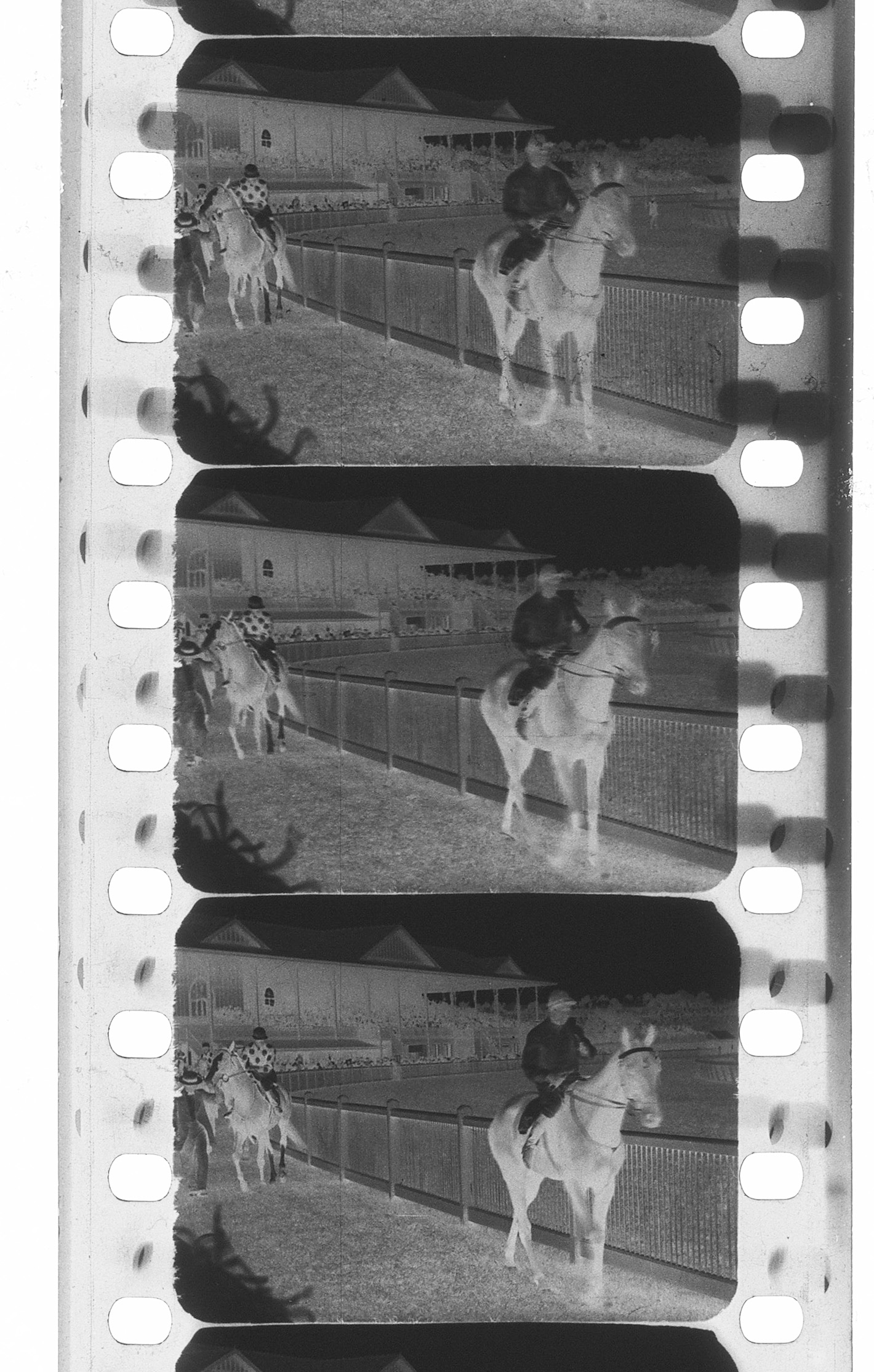

28 mm camera negative. Note: Three perforations each side.

A letter in similar vein from a Mr H I D Fraser, Purser of the TSS "Karooia" claimed that the Pathé Home Cinema carried on board for the last few trips has proved a great success in every way. "Almost every night the Pictures are screened before a large and appreciative audience and even in the large lounge of this steamer can be seen clearly and distinctly by everyone". (And all with a projector lamp of 6 volts, 0.75 amps!). The brochure concludes with a list of 207 titles available for hire.

28 mm Film Catalogues.

When one considers the number of countries in which 28 mm was used both for home and professional purposes one can assume with a reasonable degree of certainty that there is no such thing as a complete catalogue of all of the 28 mm films ever made. Most were printed down from existing 35 mm negatives but quite a lot were made using 28 mm cameras, especially in Canada. A wide range of subjects appeared on 28 mm but most of those that have turned up in the UK are educational / documentary but with a modicum of entertainment / comedy shorts. These all seem to be of either 20O ft or 400 ft in length.

In the Library of Congress in Washington DC, USA, is a large catalogue of 28 mm films, which is available for inspection on request. (They also have a Victor Safety Cinema Projector mounted on a pedestal under a glass case in one of their reception areas, Serial No. 1597).

Ref 16 states, "Fortunately for future historians and archivists, Rev. Joseph E Gravelle, a Roman Catholic Priest with a French-

Thus the wheel has turned full circle in Canada; material originally filmed on 35 mm and printed down to 28 mm is now being printed back up to 35 mm in order to project it on modern equipment.

I had the good fortune to visit the National Film Archives in Ottawa in 1983 by kind courtesy of Georde Bova, the then Head of the Film Services Unit and saw the thousands of tins of 28mm films which were still being inspected and catalogued. In addition to the collection described above the National Film Institute was still receiving a steady trickle of 28 mm films, which were being handed in by both professional organisations and private individuals as they came to light.

Subsequently Kinetopath Ltd of Film House, 251a Pitt Street Sydney, became agents for the KOK and a library of 28 mm films. (Ref 15). Their brochure stated that "a complete outfit which includes the following items being all that is necessary for the successful projection of pictures: -

The brochure contains an article taken from the "Education Gazette and Teachers Aid" of 22nd April 1914 giving details of a demonstration given including the physical demonstration given by children at the Melbourne C G, at the Education Office (Ref 9) and extolling the virtues of the 28 mm system for educational purposes. Eulogistic letters in praise of the KOK projector are reprinted in the brochure including one from the Victorian Softwoods Association of Melbourne in which the Association Secretary, Alfred R Moses, claimed to have given a show to "considerably over 200 persons present and the views were distinctly seen by all, including those at the rear of the hall".

28 mm reached Australia in 1914 and I can not do better than quote the following paragraph from Ref 9: "Education Departments in Australia had seen demonstrations of the KOK given by Pathé representatives in 1914 and, in Victoria at least, authorities accepted it as a teaching aid. The Herschell Film Laboratories became Pathé agents and carried out local processing of 28 mm films. During the 1920s the gauge enjoyed a measure of popularity such that when Pathé were phasing out 28 mm as a home movie gauge following the introduction of 9.5 mm. Herschells are reputed to have met the demand for entertainment films by making 28 mm prints of some of the American feature films that they were handling. A 28 mm film is reported to have been made in 1922 for the Victorian Education Department entitled "Fifty Years of Education in Victoria". One scene of which showed the massed children’s pageant at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Extracts from 28 mm home movies were copied for inclusion in a film made in recent years to show the history of the State Electricity Commission, and it is likely that somewhere in the Government archives are buried files detailing the early use made in this country of 28 mm film as an education medium."

In addition to obtaining prints from 35rnm originals some films were made using 28 mm cameras. Pathé Frères produced such a camera early in the history of the gauge although they are extremely rare today. Of box construction this camera was designed to be mounted on a tripod and hand cranked. The body is of wood, leather covered with a hinged front panel for access to the lens and a rear cover which hinges upwards for full access

to the rear compartment. Feed and take-

Meanwhile Pathescope of Canada had been established in 1914 with H Norton DeWitt as President and principal shareholder (Ref 14). Its initial activities had been concentrated on selling 28 mm projectors and distributing entertainment and educational shorts and features through its connections with Pathescope in the USA and the Pathé Company of France. Interest in the use of film by the Ontario Government dates from at least 1914-

A complete but not working Pathé Premier, seen at the (British) National Film Archive at Aston Clinton in 1983..

Alexander Victor tried to persuade film producers to supply 28 mm prints from their 35 mm negatives but they would not cooperate in any way. However George K Spoor of Essaney and George Kleine, both pioneers of the exhibition industry agreed to release a small number of pictures. Victor then built the first continuous reduction printer and offered it to the industry. (Ref 11). He then set up a print reduction laboratory in Chicago but he was a lone voice. The 28 mm market began to fade away due to lack of cooperation from the film producers. In 1920 Victor produced his last 28 mm projector called the Victor Home Cinema. It was a basic hand operated projector built to a very low price in an effort to keep 28 mm alive but by now it was a lost cause in the USA. (Ref 11). With the introduction of 16 mm by Eastman-

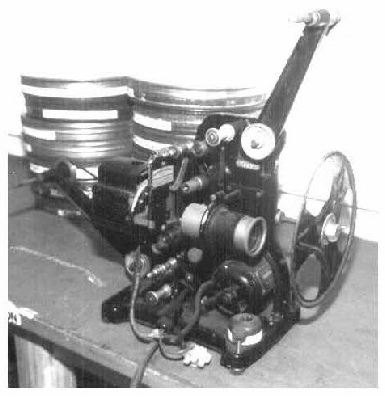

Motor driven with a three-

An interesting sideline is that it is stated in Ref 10 that toy projectors for 28 mm film were made by Keystone as well as Cummings.

Alexander Victor had also been concerned about the fire hazard of 35 mm nitrate film and in 1918 he presented a paper to the Society of Motion Picture Engineers in which he urged the adoption of 28 mm safety film by the SMPE as a new standard. This was agreed and eventually such a standard was produced by the American Standards Association. The adoption of the Safety Standard and Pathescope films by the SMPE was a vast stride forward by the industry. The new Safety Standard Film and the French Pathescope 28 mm film met with the specific qualification of the Underwriters' Laboratories and National Association of Fire Prevention which stated: "Approved miniature projectors must be so constructed that they cannot be used with films employed on the full sized commercial moving picture machine" (Ref 12).

My own Victor Safety Cinema has a small inscription on the base painted conspicuously in red lettering on a yellow background which reads: “UNDERWRITERS LABORATORIES INSPECTED”. Miniature Motion Picture Machine For Use Only with Slow Burning Film. Enclosing Booth Not Required".

The only difference between the Pathescope 28 mm standard and the one proposed by Victor was that initially his Victor format for projection prints had three sprocket holes per frame each side of the film and his projector had matching sprockets which prevented the projection of Pathescope films on the Victor machine. However, this problem was quickly resolved when Pathescope type sprockets were fitted to the Victor Safety Cinema (as is mine) and both types of projection print could be shown although, of course, automatic framing did not occur with the Victor film format.

The Victor Safety Cinema -

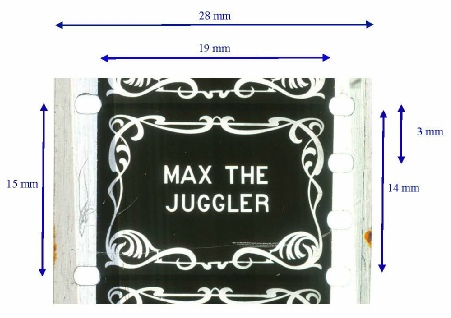

Dimensions of Pathé 28 mm film.

The Pathé KOK 28 mm projector, with its handsome carrying case / cover.

Shortly afterwards, a civil engineer in the USA, Willard Beach Cook registered the Pathescope trademark in America in 1913. At first he assembled the Pathé KOK from imported kits of parts but soon started selling machines of all American manufacture incorporating ideas of his own. The first of these new KOK machines was called 'The Popular’ which was a KOK fitted with a 12 volt 2 ampere lamp fed via a dropping resistor from the 110 volt mains supply, but it was still hand-

Next came a Motor Model for use with alternating current. This had a small single-

While all of this was happening the prolific American inventor Alexander F. Victor, well known for his earlier involvement with various devices for projecting pictures started to take an interest and became the champion of the 28mm cause in the USA. A short biography with a list of sixty-

The choice of 28 mm made it uneconomical for unscrupulous suppliers to slit down and re-

In 1912 Pathé produced the well-

It took considerable effort to wind 400 ft of film, lasting some 8 or 9 minutes at a nominal 16 fps, through the machine as I can testify from personal experience. A second French version used a large 'toast rack' dropping resistor to supply the lamp from any available 110 volt supply but the mechanism still had to be hand-

After its introduction in France the KOK projector was imported into Great Britain by Pathescope Ltd., a company set up to sell the new machine as well as other Pathescope products. The same company also opened a comprehensive library of films at offices in Piccadilly; these were released on 400ft reels. (Ref 6). However, after the KOK appeared in the UK in 1912 it was reviewed in Ref 7, which states that it was sold, by Houghtons Ltd., 88-

From the earliest days of moving pictures when Edison first showed his peepshow Kinetoscope in 1893-

Also during the early years between 1894 and 1912 a variety of now long forgotten film gauges appeared only to disappear after a short life. (Refs 1,2,3 and 4.) The purpose of these was to circumvent many of the sudden plethora of invention patents involved in the early days of motion pictures. That purpose is in no way to be related to, or confused with, the reason for the introduction of yet another gauge in 1912, that of 28 mm. This was aimed entirely at the safety aspects of film projection for non-

Charles Pathé had realised that this represented a considerable untapped market; the main obstacle to exploiting this market had been the hazardous nature of the films themselves. The advent of virtually non-

28 mm THE FIRST SAFETY FILM GAUGE

By Alan E. Lott *

FOREWORD.

During the last fifty years or so various short articles have been written about the 28 mm film gauge. A survey of these makes it clear that each one has described (sometimes incorrectly) only a small part of the overall situation, as it existed between 1912 and 1934. This review is an attempt to bring together the various pieces of the jigsaw to obtain as complete a picture as possible. However, in so doing, it has become clear that several parts of the picture are still missing, in particular, the use of 28 mm in Europe outside of Great Britain and France. I would welcome any authenticated information to help fill these blank areas.

Four of the documents I have accumulated and quoted as references (Refs 2,9, 10 and 12) are photocopy extracts and do not carry any means of identifying their source or date of publication. Apologies to the authors and publishers concerned and I shall be glad to receive the missing information.

A past article from the pages of

Reel Deals

The Pathé 28 mm camera

Film chamber of Pathé 28 mm camera.