A PAST ARTICLE FROM

REEL DEALS

The Aussie Film Collectors' Magazine

"Keeping Film Collectors in Touch"

A look at the 8mm film system in its various forms must start with the introduction

of 16mm by Kodak in 1923. Kodak’s choice of 16mm as the width for their sub-

By choosing 16mm as the width of their gauge, and not using the same perforations as 35mm, Kodak ensured that the splitting of perforated 35mm film into two lengths of 16mm was not possible, in that way Kodak was able to make the cutting down of 35mm film uneconomic and therefore unlikely.

In 1932, Kodak introduced their 8mm gauge. Their advertising of the time suggests they saw a great opportunity to put movie making into the hands of the ordinary family.Their 8mm ‘system’ was based on their already successful 16mm film and no doubt the number of Kodak film processing plants set up around the world to process it.

Kodak’s 8mm system was simple; add an extra pair of perforations to existing 16mm

film to increase the number from 40 to 80 per foot, run the film through the camera

exposing the 8mm size images down one side of the film, remove the film, turn it

over and reinsert it into the camera and expose the other half of the film. The film

was then sent off to the Kodak lab to be processed on their existing 16mm processing

machines. The 25 ft. of ‘double 8’ was then split down the middle and the two halves

joined end-

The economy offered by this system was two fold; the consumer was offered a system which gave results quite good enough for ‘family’ filming situations at close to one quarter the operating costs of 16mm, and for Kodak all processing (except the final splitting of the film) could be done of their already in place 16mm processing equipment.

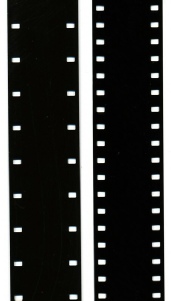

Left: 16mm film

Right: Double 8mm film

Right: Standard 8mm

camera film

Kodak and a large number of other manufacturers soon offered a range of cameras and projectors for the new gauge and it took off quickly.

At first only black and white film was available, 1935 saw the introduction of 16mm Kodachrome, just one year later it was available in 8mm – although quite expensive, color home movies became a reality.

The two sides of the double 8 camera spool.

Three cutouts on one side and four on the other prevented loading the film the wrong way up.

Although the ‘double 8’ system remained the prominent format for the 8mm gauge in the 1970s, there were various attempts to simplify the use of 8mm.

The double 8 format, although very convenient for Kodak, did have its drawbacks; in particular the need to take out the half completed film and to reload it – Kodak’s instructions to “load in subdued light only” was not always adhered to, resulting in the exposure of several feet of the valuable film at the point of loading and unloading.

Of course it should be remembered that for every foot of film fogged in this way, two feet of 8mm film was lost.

The Cine Kodak 8-

There was also the risk of the “heavy handed” reloading the half exposed film the wrong way up and exposing a new set of images over what had already been exposed.

Kodak’s answer was very simple. the camera reel design had 4 cut outs on one side and 3 on the other – in theory this would prevent the film from being reinserted the wrong way up, but loading is subdued light with big fingers and lack of patience, accidents could happen.

Contemporary reports at the time, suggest that for many people, the ‘fiddly ness’ of the operation proved quite difficult and many feet of film were lost through accidental fogging to daylight.

The Cine Kodak 8-

Other film manufacturers were already making 16mm equipmwnt, so their conversion to the 8mm gauge did not take long.

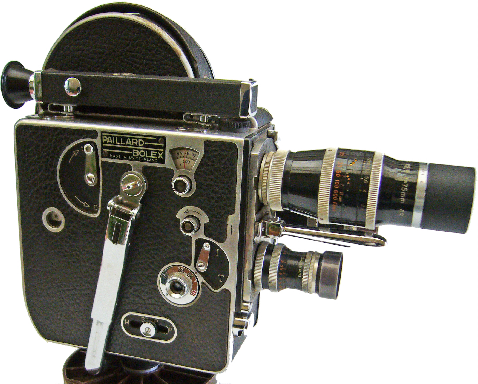

Whilst Kodak and others produced a series of 8mm cameras ranging from the basic with fixed focus lenses to the more sophisticated with interchangeable lenses, it was the Swiss manufacturer Bolex who produced the top of the range at that time – their H8.

The H8 camera with a three lens turret and had a capacity of 100 feet of double 8 film, Kodak produced a special 100 foot version of their double 8 Kodachrome for it.

Left: The Bolex H8 camera

8mm Film Formats

In 1940, Kodak introduced an enclosed cartridge system utilising their double 8 film, the film remained inside the cartridge, at the half way point, the cartridge was removed, turned over and reinserted for its second run through. The shutters incorporated into the front of the cassette ensured that no light reached the film once it was removed from the camera.

Below: Bell & Howell was one company that produced cameras for the turn over cartridge system.

Note the marking on the cartridge -

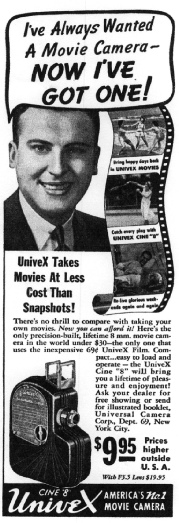

Other systems appeared over the years, one ‘loner’ was the Univex system – the company introduced both a camera and projector c1937. The camera utilised an 8mm single run film, which was supplied on small aluminium reels – neither the camera nor the film were compatible with any other manufacturer’s products.

From its introduction in 1932, until the years after the introduction of Super8,

the double 8 system was the system favoured by the vast majority of 8mm users. The

availability of Kodachrome in the double 8mm format at every camera store and chemist

shop around the country guaranteed its popularity. The enclosed cartridge formats

were certainly more convenient, but they were also dearer than the 25-

The latter years of the Double 8mm gauge saw the introduction of more sophisticated equipment. In the early 1960’s cameras with turret lenses and even zoom lenses became available. Cameras with simple sundial exposure settings were superseded by those with built in light meters and adjustable exposure settings.

Right: The Agfa single run 8mm system -

Above: The popular Bell & Howell ‘Sun Dial’ camera -

Above: The Bolex Zoom lens 8mm cine camera -

SUPER 8 ARRIVES

In 1965, Kodak launched its new version of 8mm -

The ‘new drop’ in cartridge loading arrangement was what the casual home movie user

was looking for; the ‘drop in’ style cartridge and the now automatic exposure cameras

meant that everyone could film on Super 8 -

.

The serious filmmaker soon had complaints. The torturous film path within the Super

8 cartridge meant that the film often developed a kink in it and as there was no

longer a pressure plate in the camera – it was now within the cartridge -

The introduction of Super 8 in 1965 made it necessary to differentiate between the

two non-

Today, over 40 years since its official demise, double 8mm film is still available from specialist dealers, and strangely today there are more film emulsions available that there ever was in its heyday.

The system devised by Kodak incorporated a ‘notch’ in the side of the cartridge,

which connected to a sensor in the camera. This method was used to adjust the camera

to the sensitivity of the film. As well as the very popular Kodachrome, Kodak also

made available color films with ratings up to 160 ASA. This, in combination with

the new low light cameras incorporating a 270-

Kodak produced their Standard 8 Kodachrome in two versions, the normal was for exposure in daylight and the type “A” was for use in artificial light. Type “A” was less popular, but available none the less.

With their Super 8, all Kodachrome film was produced as artificial light film. The cameras incorporated a filter in the light path, which converted daylight to the correct color temperature to suit the artificial light film loaded. This could be switched out for filming under indoor artificial light.

Left: The unusual Bolex 160 Super8 camera

Right: The camera open ready to accept the cartridge of film.

The originally released cartridge film was for silent use only.

In 1973, a new larger version of the Super 8 cartridge was introduced. The film incorporated a magnetic stripe for direct sound recording, synchronized sound recording had arrived for the home movie maker.

Left: The Japanese made Chinon Direct Sound Super8 camera.

The rival format -

In Japan, Fuji introduced an alternative format, which they called Single 8.

The single 8 film cartridge was of a completely different design. The film runs in a straight line film path, the straight line film path permits infinite rewind and facilitates ‘trick’ effects such as dissolves and double exposures within the camera.

The film was produced on a polyester base, and for the first time, amateur moviemakers were confronted with a film that could not be cement spliced. This thinner based film permitted the 50 feet of single 8 to fit onto a smaller reel that the more common acetate based Kodachrome. Film splicing also took a new direction, when Fuji introduced a tape splicer.

Above: the Super cartridge

Above: Single 8 film cartridges Left -

Above: The economy version of the single 8 range

Fuji produced a number of different film emulsions and also a sound version of their cartridge. The film format is the same as Kodak’s Super 8, so in projection, Super 8 and Single 8 are interchangeable. Although no longer generally available, both Super 8 and Single 8 film are still available from specialist dealers.

OFF SHOOTS

There was a time when Super 8 was proposed and used as a medium for such uses as documentaries and newsgathering. (Readers might remember the Australian TV series “Ask the Leyland Brothers” – well they shot their material on Super 8 film, as I recall, the image quality on their program was pretty good).

Double Super 8 film (DS8) was used in a number of high-

PACKAGED MOVIES

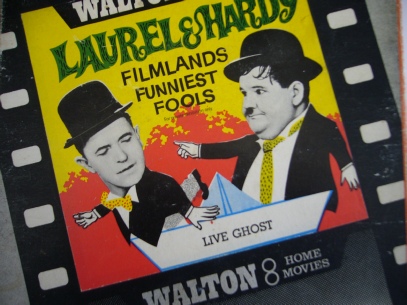

The home showman was always been keen to supplement his own movies with professionally produced films. In the Standard 8 days, a number of companies produced 8mm silent films for this purpose. Predominately Castle Films filled this market. They released a large number of films ranging from newsreels to comedy films. Many of their releases were extracts from feature films made by popular stars of the time, such as Abbott and Costello.

The latter years of the Standard 8 era saw these films released as sound versions. Standard 8 had moved into the sound era with the addition of a magnetic sound track between the outer edge and the sprocket hole.

The introduction of Super 8 coincided with the proliferation of transistorized equipment

in the electronics industry. Super 8 sound projectors became affordable and the boom

in Super 8 packaged movies took off. Super 8 releases of shorts and cartoons, as

well as feature films in both digest and full-

Copyright Mike Trickett

Geelong, Australia 2009.

All illustrations are of items in the author’s collection.

Return to Home Page

Return to Home Page