Ciné-Ducks and Dux-Cinés

Visualise a youthful projectionist setting up his ' Junior Cinematograph Picture Outfit '. He loads a film, not much over three feet in length, then cautiously lights the wick of the kerosene illuminant. Meanwhile an audience consisting of relatives and neighbours settle back in mute anticipation of the performance to come. Finally the room light is extinguished and there, on a suspended bed sheet, can be observed the faint image of a roadway.

KIDDIE

KINEMATOGRAPHS

by Charles Slater

After brief discussion the assembled audience agree that there appears to be several ducks in one corner. All eyes are now accustomed to the gloomy image and our budding entrepreneur begins cranking the handle attached to his tin-plate wonder. Miraculously the ducks begin to move. Indeed, they appear to be crossing the road. LOOK OUT! Here comes an automobile. Fortunately it just misses our feathered friends. A courteous chuckle is heard from patronising relatives at the climax of this five-second epic

To compensate for the brevity of approximately 65 frames of animation it was customary to join these short strips of 35mm film head-to-tail to create a continuous loop. Consequentially, narrowly missing disaster once was not sufficient for these foolhardy fowl; they dash forward again and escape death a second time. Then for a third, fourth and fifth time as the loop traverses gate and sprocket.

By this time hopefully Junior showman is old enough to realise that one can have too much of a good thing and a full minute of any one subject, even if as thrilling as these dare devil ducks, is usually sufficient. Room lights go on to enable a fresh subject to be laced up. What will it be next? ‘Crashing Waves’, 'Boxing Match’ or that sure-fire hit - ‘Approaching Train’.

Right: Typical Child's Cinematograph Outfit

Motion picture repertoire exhausted, versatility of the apparatus is demonstrated by using it to screen ‘stereopticon views’ ( translation - ‘glass slides’) in full lithographic colour, concluding with some from the ‘Comic Faces’ series, each guaranteed for a good laugh. Finally, the show over, the lad's proud parents are assured by departing guests that their budding showman has a brilliant future.

In today’s high-tech society a few seconds of barely discernible animation flickering on a suspended bed sheet would hardly be considered an evening’s entertainment. However, for many of us, born in the pre-TV era this was our first experience of movies at home. Proof that there was a time when such simple diversions were popular is evidenced the hardware and software that still survives.

A wide variety of these toy projectors have been produced over the years. They came in numerous sizes, shapes and colours even though, for the most part, sharing basic operating principles. Most turn-of-the-century examples were, like many other tin toys of the period, of German origin. Made of ‘Russian Iron’ by the Nurernburg firm Bing, they spread throughout the world under a variety of aliases. The light source was usually a small kerosene lamp complete with chimney. Optics consisted of an elementary condenser lens behind the film gate and a single meniscus projecting lens, fitted in a sliding barrel for focusing. These were basic requirements for both still (magic lantern) and movie (cinematograph) projectors. Additional mechanics necessary for movie versions consisted of the hand cranked intermittent movement, usually a toothed wheel driven by a crude ‘Maltese cross’. An alternative was an even more fundamental ‘beater’ movement; a rotating bent rod, which literally bashed the film through a frame (or so) at a time. Geared to the intermittent movement was a rotary fan type shutter (usually single bladed). Cheaper versions dispensed with this technical nicety thereby increasing the marginal light output at the expense of severe ‘ghosting’ (vertical smearing of highlights). A guide was provided for the film loop consisting of a vertical rod with a top right-angle bend over which the film would travel.

Film subjects were usually simple line-drawn animations in either black and white or lithographic colour. As explained earlier, the brevity of scenes was overcome by joining the ends to form a continuous loop. Longer films, of 30 feet or more, were also available, but all examples I have seen thus far consist of discarded lengths of commercial feature film. Toy shops sold these rolls in appropriately sized cans for a few pennies each. Being inflammable nitrate based film, most of these ended up as 'stink bombs' at the hands of schoolboys whose interests lay less with film techniques than pyrotechnics. What remains has usually gone the way of most nitrate silent film, shrunken and decomposed. The shorter acetate loops have usually become too brittle to stand projection without disintegrating.

Although many thousands of playroom projection devices must have been manufactured over the years a mere fraction endured the passage of time. This is no doubt due to the flimsy construction of these devises coupled with the harsh treatment dished out by their youthful guardians. This applies even more in the case of the primitive ‘software’

Films made specifically for these machines were of standard 35mm gauge but printed mechanically (i.e. not photographically), on a slow burning base. It is a wonder that any examples of these frail strips remained intact after suffering numerous passes across those rudimentary sprockets in such close proximity to a naked flame. (Perhaps there could be merit in reprinting these examples of these embryonic motion picture cartoons while some still survive).

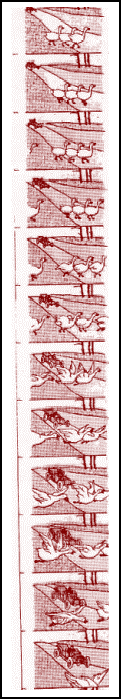

Right: German Made DUX KINO with 35mm Strip of 2 Phase Animation

After World War I at least two toy projectors were manufactured, which ran 28mm film, apparently to use up leftover stock of this obsolete Pathé gauge. Later, Japanese manufacturers copied the products of Bing and others with brand names such as ‘King’, ‘Lion’, and ‘Fairy Maid.’ Usually, these imitations were even less sturdy than the German originals. These factors combine to place toy cinemas in the scarce, although not rare, category. Such scarcity is possibly more evident here in Australia due to the sparser population and cultural leaning toward outdoor recreation. Aussie Christmas stockings were far more likely to include a cricket bat than a magic lantern. For anyone with regard for the history of cinema technology or a passion for collecting juvenilia, such items are intriguing. Little wonder, with my wife keen on the latter and myself with film dust coursing through my veins, we are forever on the lookout for unfamiliar toy projectors.

As a further attempt to justify this odd habit, I must add that, as a youngster growing up in the early '50s, I did at various times own latter-day equivalents of those elementary projectors. A misspent youth, drooling over ads for cinematographs, 3D Viewers, film strip projectors, in fact anything that used film or slides, created an ongoing addiction that still demands occasional gratification. This infatuation with cinematic toys began, not with the tin-plate and kerosene lamp variety, but with a latter-day Bakelite counterpart which ran on batteries.

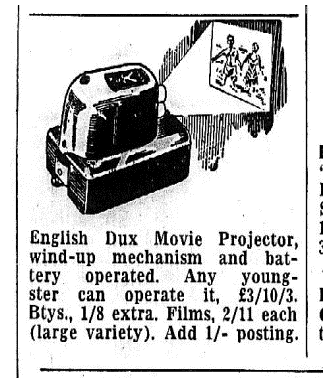

For some months during 1950-51 the back page of the Australian magazine "Radio and Hobbies" carried an advertisement for a quite fascinating toy called the ‘Dux Movie Projector’. Precious little information was given other than that it was English built and cost, in those pre-decimal currency days, £3/10/3 and there were a ‘wide variety of films available at 2/11 each’. When eventually, a Dux Cine (to give it its proper designation) turned up in the window of a local toyshop, it was LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT...

Left: Levenson's 1950 advertisement in Radio & Hobbies for the British Made DUX CINE

Much time was spent after school, nose against the store window, trying to figure out the operational details of this curious battery and clockwork operated device. It was an occasion for much excitement when a cousin and I, between us, eventually managed to save the requisite sum and purchased our very own movie projector. Over the next few years I acquired several other simple projectors, eventually ending up, at age 16, with a ‘real proper’ 8mm Eumig. By then I would never have believed that, around 15 years later, unearthing an example of that long since disposed of Dux would become a burning ambition. As the accompanying photos suggest, my search was ultimately successful.

THE 'DIN' DUX

I have unashamedly confessed to a fondness for cinematic hardware of the most elementary kind. In the process of satisfying this irrational urge to accumulate examples of bygone toy projectors I discovered one of my favorite childhood toys the DUX CINE had ancestors going back to at least 1929.

Chicko Marx once quipped “Why a duck?” More to our point: What is a Dux?

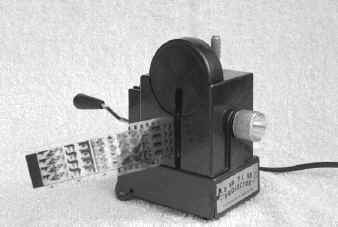

Actually, the Dux projector was neither a bona fide movie nor a conventional still filmstrip projector, but fell into a category somewhere between the two. It’s principles owed much to the early dissolving ‘biunial’ lanterns of which it was a miniaturised mechanical version. The Dux employed twin optical systems, two lenses, two battery-powered lamps and clockwork driven switch that alternately lit one or the other.

Pathés original 9.5mm notched title film system was incredibly economical, but the Dux did much better. This diminutive toy actually managed to realise nearly two minutes of ‘moving pictures’ from a mere twelve inches of 35mm film. The foot long film, which was advanced by the clockwork motor travelled horizontally at a literal snail’s pace past the dual apertures. It consisted of pairs of images, one above the other. These depicted the two extreme phases of a repetitive action. As the two images were projected alternately about once a second, an illusion of limited yet comically quaint animation was achieved. A continuously moving panorama of

such scenes appeared on the screen due to the filmstrip’s slow but continuous passage through the projector. Subjects included stock nursery stories such as Red Riding Hood, simplified versions of Disney-type characters and classics such as Robinson Crusoe, the latter requiring three strips - quite an epic.

It may be worth noting at this point, before some reader alleges my observations are amiss regarding such details as the precise designation of this projector, that my Dux Cine had a close (but not identical) twin. This was the Dux Kino manufactured in Germany and marketed, both in Australia and Britain, concurrently with it’s British made counterpart. The differences were subtle but worth pointing out.

In a way the Dux Kino was a DIN version of the Dux Cine. Although externally the most obvious difference is in the logo embossed on top, the Kino mechanism actually transports its film in the reverse direction to that of the Dux Cine. The result is that, although the films made for each machine are essentially compatible, captions on strips made for the Kino appear back-to-front when run on it’s British counterpart and vice-versa.

This is slightly reminiscent of the situation that occurred in the early 1930’s with the introduction of 16mm ‘talkies’. Films made for a SMPE standard projector, such as the British Thomson Houston, would appear left-right reversed if run on a German DIN standard machine. (See Gerald McKee’s account in ‘THE HOME CINEMA’ for further details).

Above: British Dux Cine and German Dux Kino. Note the winding keys are on opposite sides due to the inversely mounted mechanisms.

The other major dissimilarity is internal. The Dux Cine utilises a simple rotary switch arrangement to alternately power the two 3.8 volt torch globes thereby producing the requisite dissolve effect. The Kino on the other hand makes do with a small rotating shutter blade to give the same effect. Consequently power is applied to both light globes at once, effectively halving the life of the 4.5-volt cycle lamp battery.

The Mini Cine

Another projector, more or less contemporary with the Dux but slightly more advanced, was the London manufactured MiniCine which first made its appearance circa 1949. Lacking the Dux’s clockwork transport the MiniCine had to be continually hand cranked. It did however offer four phases of animation as compared to the two carried on the identically sized Dux filmstrip. It is interesting to note that this device was never referred to in any advertising as a toy. Apparently, in Britain at least, there was a taxation advantage in marketing this machine as a real projector.

An exhaustive treatise on the history and mechanics of the MiniCine can be found in the set of papers privately published by Stephen Herbert some years back under the collective title ‘Amateur Cinematography’.

Last year I acquired a North American version of the MiniCine put out under the name of the Disney-Land Projector manufactured by Mavco Inc., N.Y.C. Although operating on the same principle as its British equivalent, this projector is totally different in appearance.

Above: the MiniCine loaded with its 4-phase filmstrip

Approximately four inches high and more or less box shaped, it is topped off with a semi-circular simulated spool box which has no purpose whatsoever other than to make it look more like a ‘reel (sic) projector’. The body is entirely plastic unlike the totally cast aluminium MiniCine. The mechanism of the Disney-Land Projector, although fundamentally similar to the British version, it appears not near as robust. Although it does boast a larger light source (a car automobile type panel lamp as opposed to the torch globe used in the MiniCine) there is little difference in screen brightness.

There was a rudimentary shutter fitted, made of gray translucent plastic. I say was fitted as the heat of the lamp had distorted it almost beyond recognition. Not that it would ever have been very effective, as it was the sort of shutter a designer might specify if he was unsure whether a shutter was necessary. Being translucent and with its under-size blades, in relatively sharp focus, the presence of this shutter would be only slightly less disturbing than the streaking highlights it was intended to alleviate.

The gate aperture in the US model is slightly less high than that of the MiniCine yielding an aspect ratio of 1 to 1.7, (very close to the current standard cinema ‘Wide-Screen’ format) as opposed to the MiniCine’s 1 to 1.5 ratio. Both these wider than normal formats were the by-product of fitting four images (sideways) into the space of a normal 35mm ciné frame. As Stephen Herbert described in his aforementioned paper, there was a ‘super’ model of the Mini-Cine that boasted an adjustable aperture. This allowed the projection of competing brands of square (1 x 1 ratio) still filmstrips.

The U.S. manufactured Disney-Land projector,

which utilised the same film format as the mini-cine.

The one film that came with the Disney-Land projector was a slightly faded colour (Eastman Color?) strip of ‘Bambi’. I found it intriguing that this version was completely different to the Bambi film supplied for the MiniCine. If there were any affiliation between the manufacturers of these two machines it would seem to have been rather tenuous.

As for the coloured Mini-Cine filmstrips, many seem to have retained their original colours perfectly while others (such as those edge-marked ‘Dufay Chrome’) have faded to a magenta monochrome. Curiously, the dreaded wording ‘Nitrate film’ appears along the edge of a few of these films, however this apparently emanates from the original master; the end product was undoubtedly acetate safety film.

I have often wondered ‘who copied who’ in the conception of these limited animation projectors. The Dux Cine apparently had an all metal antecedent in The Baby Cine. The only example I know of being one I sighted some six years ago in the Buckingham Movie Museum. My all too brief visit precluded detailed observance of any one of the multitude of rarities on display however I did obtain the impression that this was an earlier design than the Dux. Is there a reader out there who can provide some facts on this device?

One thing appears certain; all of the toy projectors mentioned so far had ancestors going back to around 1930. What is perhaps more intriguing is the fact that during that time examples were being marketed which boasted ‘synchronised sound’, albeit of the lowest imaginable fidelity.

IRVING BERLIN AND THE TOY TALKIES

Back in the mid-1930’s there were several toy ciné projectors manufactured under such names as the Movie-Jector, and NIC which used the same basic principles as the later Dux Cine/Dux Kino but utilised a three inch wide paper roll bearing dual images instead of a 35mm film -strip. They were usually printed in two or three colours, although I have seen one black and white example. Lit from behind by an illuminant consisting of a 25-watt domestic light bulb, these films yielded a reasonable brightness with a projected image approximately 18 inches wide. Being translucent, the paper roll acted as its own diffuser and no condenser lenses were required.

The projectors were of tin-plate construction and, like the later Dux, utilised twin lenses in a ‘biunial’ configuration. A pair of ‘front shutters’ alternatively revealed the top and bottom row of images while the mechanically linked take-up spool transported the strip horizontally.

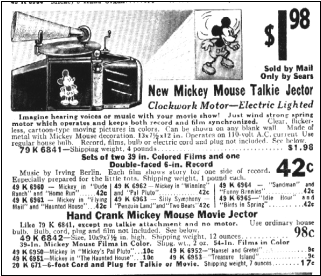

Some models featured a crude toy gramophone coupled to the film transport mechanism that provided ‘sound movies’. The earliest printed reference to one of these I have so far sighted was in a 1936 Sears Roebuck catalogue. The device was the ‘Mickey Mouse Talkie Jector’ and was available in both sound and silent versions. Being an avid collector of odd-ball sound recordings as well as cinematic objects, I was highly intrigued to find these existed and eventually managed to procure an example, albeit in ‘extremely distressed’ condition. Still it was enough to prove that such devices were sold and I now aspire to acquiring a more restorable example ideally with some picture rolls and corresponding disc records.

(Since penning the above, the author has realised this ambition and his collection is ‘now complete’. - “Oh yes? How often have I heard that?” replies his long suffering wife).

Above: From a 1936 Sears Roebuck catalogue; the Mickey Mouse Talkie Jector

About the time my Mickey Mouse Talkie Jector turned, up a Phonograph collector friend revealed he owned a similar toy simply designated the Talkie-Jector. The fundamental difference between it and the Mickey version, was that it had a manivelle mechanism (music-box collector’s jargon for ‘hand-cranked’) as opposed to the clockwork drive provided by the Sears ‘Mouse’ Talkie Jector. My friend has several filmstrips for it and, most intriguingly, a few of the six-inch soundtrack records. The discs are double sided and play at the once customary speed of 78 rpm. Both the paper strips and accompanying discs are compatible with those of the Sears projectors and were most likely manufactured by the organisation.

The quality of the midget soundtrack discs is quite good when played on a conventional gramophone. Unfortunately the hand turned player attached to the Talkie-Jector is extremely irregular in speed as well as minimal in its fidelity, the horn being much too short to produce decent volume or acceptable bass response. The result is that speech is barely intelligible while the musical background is totally obscured by wow and flutter.

This makes ironic an assertion found in the Sears advertisement that the music on these recordings was composed by none other than Irving Berlin. One can’t help wondering how a composer of this stature could become involved in such an apparently low-key project?

Listening to my friend’s examples of these records on reasonable equipment reveals, to my ears at least, a musical underscore that is both competent and original. There is however no mention of the composer on any of the labels. All a bit puzzling wouldn’t you agree?

The Talkie Jector

During the last few years it has become quite obvious to me that there have been many other makes and models of toy projector utilising the same principles of two phase animation. Just how many, I am a long way off establishing. So far I have seen, or at least heard of, about half a dozen others in addition to those mentioned above. One example is the ‘Uncle Sam Durotone’, manufactured by the ‘Durable Toy and Novelty Corp. 200 Fifth Avenue New York. This was a gramophone/projector combination with an oversize paper diagram in place of the usual soundbox/horn assembly

This is possibly the earliest; (it sports a 1929 patent date. It would appear that the Spanish toy factory NIC (named after its founder: Nicolau Riba) was the originator of this style of movie projector. It was also manufactured in the USA and France. The NIC came in a variety of shapes and sizes some, once again, with coupled gramophones. There was even one Spanish NIC that provided musical accompaniment, not from a gramophone, but from a simple reed organ under control of perforations on the picture roll!

Right: The Spanish NIC 'talkie' Projector for 40mm paper film (incompatible with U.S. machines)

Later variants include the French Selic manufacturer’s ‘Midi-ciné’ (circa 1960), while from Germany came the ‘Lilliput’ and the ‘Duxette’. All these utilised ‘Dux Kino’ type 35mm films.

Hopefully, enough will be known soon to establish a definitive history of the rise and fall of these quaint toys. If any reader has further details (or questions) on any toy cinemas I would certainly be delighted to hear from them.

All of which I guess brings me to my present situation. Here I am, over 60 years old and earnestly accumulating examples of toy projectors, many of which I would have been embarrassed to be seen with during my teenage years.

Well I suppose; nobody's perfect.

Above: The French made 'Midi-cine' projector and films

Copyright Charles Slater 2001