Page 34 - RD_2021-03

P. 34

REPRINTED FROM - HOME MOVIES & HOME TALKIES, August, 1936

Things That Were !

By Colin Bennett, F.R.P.S.

When first I took a practical interest in cinematography, about the year 1909, the Cinematograph

Act had not come into force. Anyone possessing a projector could set it up where and how he

liked, and run the flammable nitrate film through it into an open wastepaper basket, or on to the

floor if he chose. The illuminant was nearly always limelight and, to save the heavy cost of

carriage on a coal gas or hydrogen cylinder, its place was often taken by an ether saturator; a

heavy metal box stuffed with tow having a suitable tap-controlled inlet and outlet.

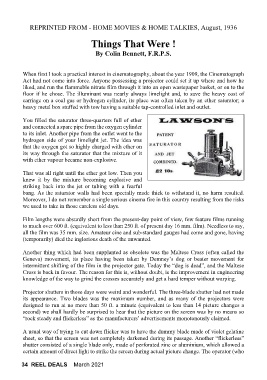

You filled the saturator three-quarters full of ether

and connected a spare pipe from the oxygen cylinder

to its inlet. Another pipe from the outlet went to the

hydrogen side of your limelight jet. The idea was

that the oxygen got so highly charged with ether on

its way through the saturator that the mixture of it

with ether vapour became non-explosive.

That was all right until the ether got low. Then you

knew it by the mixture becoming explosive and

striking back into the jet or tubing with a fearful

bang. As the saturator walls had been specially made thick to withstand it, no harm resulted.

Moreover, I do not remember a single serious cinema fire in this country resulting from the risks

we used to take in those careless old days.

Film lengths were absurdly short from the present-day point of view, few feature films running

to much over 600 ft. (equivalent to less than 250 ft. of present day 16 mm. film). Needless to say,

all the film was 35 mm. size. Amateur cine and sub-standard gauges had come and gone, having

(temporarily) died the inglorious death of the unwanted.

Another thing which had been supplanted as obsolete was the Maltese Cross (often called the

Geneva) movement, its place having been taken by Demney’s dog or beater movement for

intermittent shifting of the film in the projector gate. Today the “dog is dead”, and the Maltese

Cross is back in favour. The reason for this is, without doubt, is the improvement in engineering

knowledge of the way to grind the crosses accurately and get a hard temper without warping.

Projector shutters in those days were weird and wonderful. The three-blade shutter had not made

its appearance. Two blades was the maximum number, and as many of the projectors were

designed to run at no more than 50 ft. a minute (equivalent to less than 14 picture changes a

second) we shall hardly be surprised to hear that the picture on the screen was by no means so

“rock steady and flickerless” as the manufacturers’ advertisements monotonously claimed.

A usual way of trying to cut down flicker was to have the dummy blade made of violet gelatine

sheet, so that the screen was not completely darkened during its passage. Another “flickerless”

shutter consisted of a single blade only, made of perforated zinc or aluminium, which allowed a

certain amount of direct light to strike the screen during actual picture change. The operator (who

34 REEL DEALS March 2021